The Inside Zone

In the last few articles, I’ve covered some of the basics of the Inside Zone for Offensive Line, players and coaches. It’s pretty technical and founded on a lot of hard work and studying, as well as a fair bit of trial and error.

In this article we’ll look at some of the basics of running the inside zone, from a co-ordinator’s standpoint, and some of the variations you can use to make a simple Inside Zone play, a big part of your offense.

Let’s first look at some small technicalities, regarding Running Back entry point, and what this does to the defense.

For the purposes of these diagrams, I will draw them all out of a spread, under centre look, and we will look at different formations later on.

Aiming Points and Entry Points

Whilst there is only a very subtle difference in terminology here, please clear, they are two very distinct things.

The Aiming Point, is the visual key you give the Running Back to aim for.

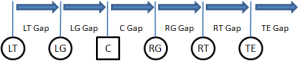

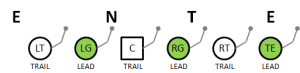

The Entry Point is the Gap you are expecting to be open based on the defensive front.

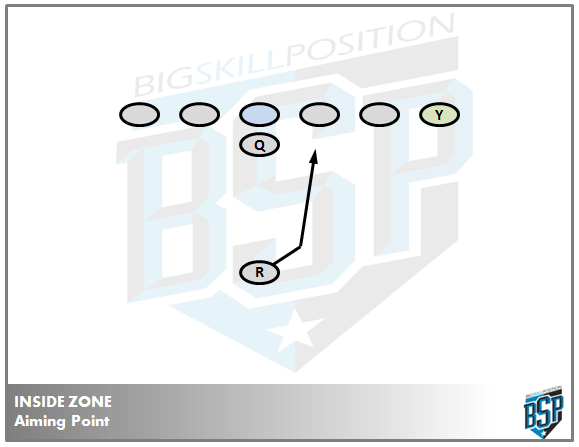

Aiming Point

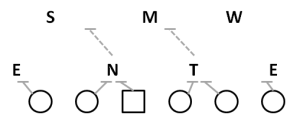

The Aiming Point for Inside Zone can be anywhere from the Centre’s playside butt cheek, to the outside shoulder of the playside guard, it very much depends on your players, offensive style and what you are trying to accomplish.

For me, I like the Running Back (RB) to have an aiming point at the middle of the Playside Guards’ (PSG) butt.

This allows the RB the best post-snap read of the play developing in front of him, before he makes his cut. The idea is to aim for the centreline of the PSG, to give an entry point of the PS A Gap. However, we all know this depends on a few things, mainly the defensive front, so this leads us on nicely to the Entry Points.

Entry Point

The entry point is the hole/gap the running back attacks as he explodes through the line. The Aiming Point gives the RB a track to work on, the Entry Point is the entry point through the line of scrimmage, and these are different things.

The entry points will vary based on the defensive front, but if you give the RB unlimited options in where to go with the ball, chances are he’ll over think it, and you’re not going to get many gains from that play.

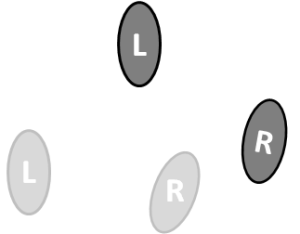

So we have reduced the running backs options to 3, and we use an easy to remember verbiage to instil these options into the RB’s mind.

BANG IT – Hit it in the Playside A Gap – This is the ideal scenario for us.

BEND IT – Bend it to the Backside A Gap – we band it if the playside A Gap has been crashed or filled

BOUNCE IT – Bounce it to the Playside B Gap or wider – We bounce when the middle is clogged up.

Please note, I have drawn the Running backs aiming point and entry points correctly, but I haven’t shown the OL movement.

We, and countless other teams have found that the BANG, BEND, BOUNCE concept for running backs speeds up their reads, and results in greater gains for your Inside Zone plays.

The window dressing and various options when running IZ

At a coach/coordinator level, we must really start to think about the window dressing we use around these plays. I mean formations, motions, reads, triple options, these are the thoughts that need to go through your head when game planning for your opponents.

Do you have a TE, can he also play FB, do you have 2 FB’s, can you go empty and run your QB?

All of these are possibilities, using the exact same blocking scheme and play nomenclature. So let’s have a look at some of the options available to you.

Spread Offense Zone Packages

As the spread offense becomes more and more prevalent throughout football, especially college football, the advances and innovations to the inside zone have become one of the biggest parts of the game. Let’s look at some of these innovations.

[NB: When I say spread offense, I use the term loosely, as you’ll see from some of the examples I’ll use, I have covered off a myriad of different offenses under the spread offense banner. This is a deliberate ‘mistake’ for ease of writing and reading, I’m fully aware of the many different brackets and types of offenses run today.]

Singleback Zone Read

Let me start by emphasising the fact that this is not called ‘read option’, the read is the option, calling it read option infers a triple option threat, i.e the read, then the option, and that is covered under triple option below.

Rich Rodriguez is credited with creating and utilising the zone read during his times at Glenville State, Tulane, Clemson and most famously with Pat White at West Virginia.

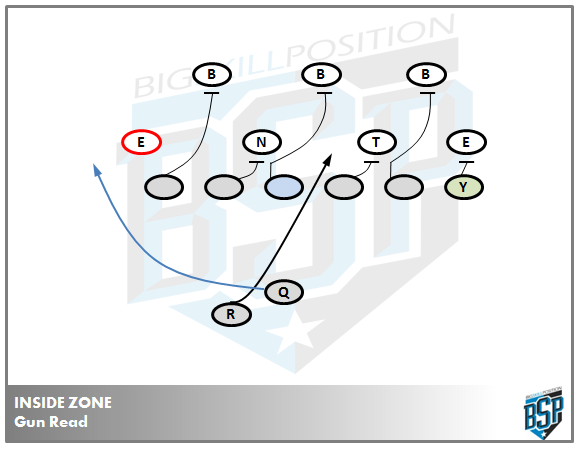

The zone read uses the standard inside zone blocking rules as identified in previous articles, but also utilises the quarterback as a running threat.

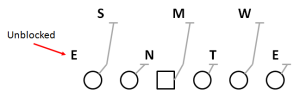

You can see in this example, from a standard shotgun set, the QB uses the backside defensive ends alignment against him, and simply ‘reads’ what he is doing, it provides a very simple rule for the QB:

If the DE goes upfield – GIVE the ball

If the DE crashes – KEEP the ball

Obviously this has been massively successful throughout all levels of football, and has been modified to do the same thing out of the pistol formation too, as can be seen below:

This option was first used by Chris Ault at Nevada, notably with Colin Kaepernick at quarterback, and was extremely successful, here is an example of the ‘Snatch’ technique they talk about. Whilst it looks like a read, the reality is the don’t read every play, they tag when they want to read and when they don’t, but use the same technique throughout.

This allows us to keep 6 on 6 blocking the Inside Zone play, whilst reading the backside DE.

What we have seen over time is defense becoming more aware of these schemes and evolving, either teaching the DE to ‘slow play’ the read and delay the QB’s decision making, or through gap exchange with the DL and LB’s.

This leads on to the next development of the Zone Read

2-Back Zone Read

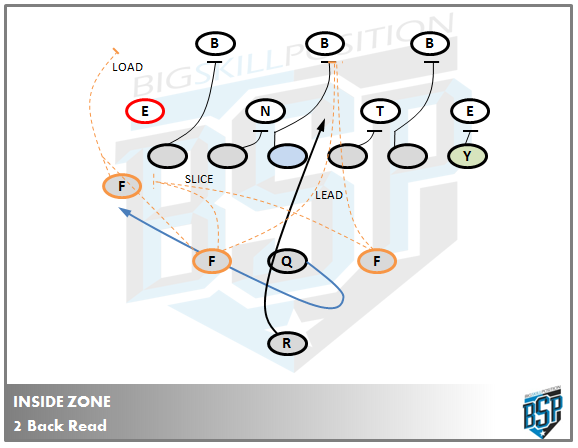

The 2-Back Zone read game allows offenses to better match up to good defenses, and it provides a vast array of options that can be added to your game, to really mix up your play calling.

For example, if you take the standard shotgun zone read above, and add in a Fullback/H-Back, you can make the same play look so very different to the defense. Multiplicity with Simplicity!

You can call:

LEAD – Tells the Fullback to lead through the PS A Gap

SLICE – Tells the Fullback to block the Backside DE

LOAD – Tells the H-Back to leave the DE and block first force defender.

If the above is “Pro Rt. 22 Zone”, we can tag the fullback to give us very different looks, yet highly successful plays.

“Pro Rt. 22 Zone ‘Lead’” – we now have 7 v 6 blocking at the POA

“Pro Rt. 22 Zone ‘Slice’” – now we can still read what the DE does, but we have a body blocking him. The same read rules apply as before, but now if the DE goes upfield, the QB keeps it and runs off the FB block.

“Flanker Lt 22 Zone ‘Load’” – Now if the read dictates the QB keep the ball, we have an additional blocker in front, taking the first force defender.

The real benefits to this type of zone read is the seemingly multiple plays you can run, and run well, with a minimal installation time. This is absolutely vital, especially for coaches in Europe and High Scholl coaches who have very little time with players.

Again, we can see the same options available from a pistol set:

I’ve shown the Fullback or H-Back in multiple positions on these diagrams, but obviously only 1 position would be used.

You can immediately see some of the benefits 2-back sets have in the read game, especially when it comes to multiplicity. I’ve explained the 3 different types of plays, but think of the formation you can run them from:

King (Fullback to same side as TE)

Queen (Fullback opposite the TE)

Flanker (Fullback aligned in a wing position)

Trips (2 receivers and TE on the same side)

Wing (Fullback aligned outside the TE)

Pro (Split backs)

These are the top formations that these plays are run from, and we can see that through installing the Inside Zone concept, we are learning one concept, whilst making the defense prepare for 18 different looks. It’s a very powerful concept to use.

Pro-Style Zone

One of my good friends, and former coaches, is Coach Stephen McCusker, who is one of the most respected coaches in Europe.

He is one of the few British coaches to coach at the professional level, as Special Teams Coordinator o f the Scottish Claymores, at international level, as the Offensive Coordinator of the Great Britain Lions for many years, at the youth level, with Team Scotland, and at the Senior level, in his current role as Special Teams Coordinator of Premier North Champions the East Kilbride Pirates.

Coach McCusker has kindly put some notes together about the Pro-Style Inside Zone he likes to run, some of the variations and has had much success with over the years.

Coach likes to have his aiming point as the first defender past the centre, and he prefers to run it at the B-Gap defender.

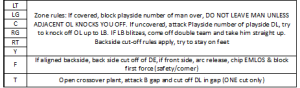

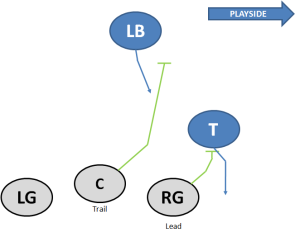

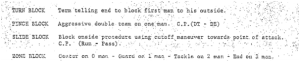

Here are Coach McCusker’s rules for the OL, FB, Running Back (Tailback here) and Tight End.

The base play here will end up looking like:

You can see, as we are lined up in a Weak-I formation, the FB has the backside cut-off of the DE. This allows for the OL and Tight End to be able to block 6 v 6 in the middle, a strong position to be in.

Coach also has a ‘plus’ tag for the FB, which can be used if the first force player is disrupting the play, and cannot be blocked by the WR receiver (Note: adding the plus tag also allows tells the WR to block second force)

This allows for us to gain an advantage and load the playside ending 7 v 6 in the box in some situations, as shown below. Obviously this is a nice change up to initial ‘Minus’ or ‘Slice’ blocking by the FB.

Coach McCusker emphasised the importance of the QB boot “The QB owns the backside DE on the boot (also EVERY time he hands off on the zone). The QB gets his head around and finds the BS DE. He should be able to tell the coach where he is and when he should start to think of calling the boot”

The Zone Package

One of the big things coach preaches is not just having an inside zone play you are committed to, it’s having a package of plays to compliment and work off the base zone play. Having variations on it.

Whether it’s from a single back or 2 back set, spread or trips or double tight. These are all simple, easy to install options that keep the defense guessing and keep your offense fresh.

Adding in Boot, Slice and Reverse are all plays that coach likes to use as part of his ‘Zone Package’ and add a powerful play action passing game to your offense.

“Strong Rt. Open Boot Lt. Slice”

One of the main coaching points here is to look at the QB’s progression, from Flat to Over, rather than working from deep backwards. Something Coach McCusker emphasised with this play is his philosophy of always take the completion first.

“Weak Rt. Open Boot Lt.”

“Trips Rt. Zone Rt. H Reverse”

“On the reverse..” McCusker states “The QB fakes zone, then the Slot in Trips comes back behind the QB to fake or take the reverse. The QB then settles straight back to set up to throw (behind the B Gap).

The OL run the Zone, but the BST loops round and ambushes the BSDE, or if he bites, leads up on the OLB on the side.”

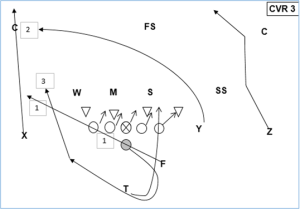

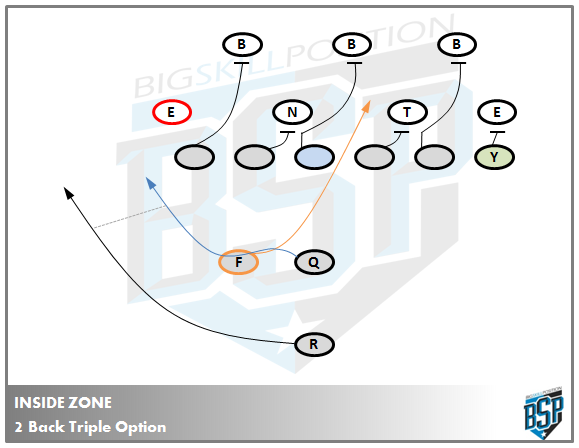

Triple Option

The triple option has been around for years, and will continue to be so for many years, for one major reason. It works!

Again, this is building from what we have seen in the single, and two-back variations of the inside zone, and looking at just a few of the possibilities open to you by utilising the Inside Zone.

Here we can see we still have the regular Inside Zone read with the FB in a shotgun alignment, and the Running back becomes the pitch man in the event of a keep read. In these cases the read man is the backside DE, and the pitch man will be the first force player, likely to be a safety.

This is an excellent play call with a running quarterback and/or against a good gap exchange team also.

If you have different personnel groupings you can also substitute in your #2 back to act as FB and take the handoff. It’s just another way to get your best athletes on the field.

Here is an example of a variation on the Inside Zone Read. Again, this is a very good play to run with 2 RB’s on the field.

It’s also possible to put motions into these plays, and you can see the immediate benefits to that also.

Finally, and a bit more outside the box thinking in this one, is using the WR as the pitch man, as you can see here. It’s a play I would run more to the boundary than the field due to the width of the receivers, but is extremely easy to swap sides.

For example, I have shown Spread Rt Triple Option Left. We could just as easily run Spread Rt, Triple Option Right.

In that case the DE over the TE would become the Read man, and the corner over the Z would be the first force, or pitch player.

As you can see, one of the focuses of modern day football is to run the same play, but get the defense to react in different ways to that play. Above I have shown how we can do that with single back, 2 backs, pro style and finally, the triple option.

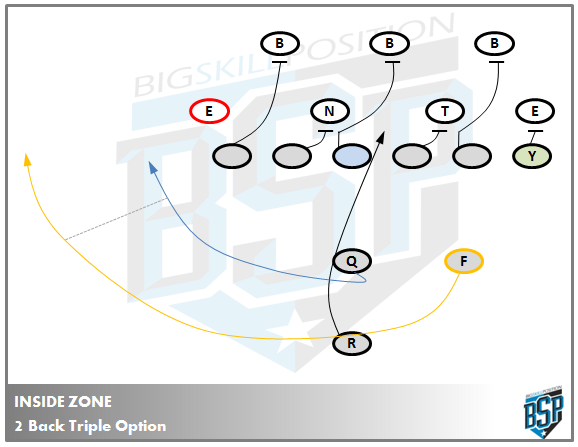

Below we’ll now look at one of the newer facets of the game, combination or packaged plays.

2 in 1, 3 in 1, 4 in 1 plays

Combination plays are a relatively new invention, which seem to be credited a lot to Dana Holgorsen from his time at Oklahoma State and now West Virginia.

The essence of these plays is a numbers game, based on the number of defensive players in the box, if there are less than 6 players in the box we run the ball, 6 or more, we look at passing.

As we can see above, it’s a concept as old as the spread offense itself, and worked for a long time, until defenses started shifting their methodology, why should they give them a clear read pre-snap?

So defenses started becoming more mobile, OLB apexed and blitzed, with the safety rotating down, confusing the QB’s read, and resulting in tackles for a loss.

As a way to solve this, we can now incorporate a Bubble Screen or Fast Screen (Outside Receiver Screen) onto the backside of zone run concepts, especially out of Shotgun or Pistol sets.

Here you can see, we have turned the Apex defender into a read. If he turns his hips, to drop to his passing zone, we give the handoff, if he stays to play the run, we throw the Bubble. A very simple and easy to install play onto your existing zone play.

Here we can see some clips of this play at the NCAA level. You’ll notice how easy it is to add in motions to fully utilise your existing formations, and still have the same concept being run.

But what if you have an athlete at Quarterback and you don’t want to lose him as a threat?

3 in 1

We can take the simple play demonstrated above and add in a zone read with the QB. Like so:

or in the NFL (with what I would say isn’t the most athletically gifted Quarterback ever seen):

Here we can see the play drawn up, and can easily dissect the options available:

1. DE plays upfield, forcing the GIVE to the running back

2. a) DE crashes in forcing the KEEP, then the force player is covering the Bubble, so remains a KEEP.

2. b) DE crashes in forcing the KEEP, then the force attacks QB run, so throw the Bubble.

This is good play to throw in and mix it up with the other plays described above.

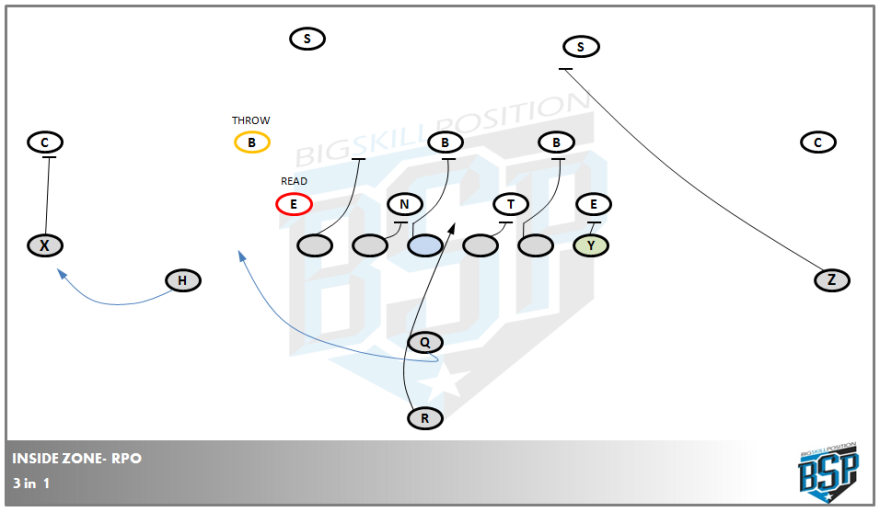

4 in 1

Credit here must go to Hugh Freeze, not just for having one of the coolest names in football, but for really understanding this concept and how it can work.

The 4 in 1 takes all the advantages of the 3 in 1 play above, and adds in a backside curl route as the 4th option.

This really pushes the whole “Numbers” game to a whole new level. Essentially the reads now become:

<6 defenders in the box = Run the Read option

6 or more defenders in the box = Pick the best option between Bubble or Quick Hitch.

And it really is that simple, as you can see here:

What this clip demonstrates is that you can leave this one play on the pitch, and run it multiple times quickly, forcing the defense to stay in the same personnel and likely, front.

You can see above, Ole Miss run this play 5 times in a row, and score on the final play. That’s 5 plays in 1:27 real time! That’s tempo.

This article is by no means an exhaustive list of all the ways to run Inside Zone, more a suggestion at some of the ways I’ve seen work, and a brief explanation of them.

Summary

What I have tried to show above, is by no means an exhaustive list of all the ways to run Inside Zone, but instead a series of ideas of how to open up your playbook to incorporate the zone, and make things simpler for your offense.

Adding in constraint plays like the bubble is a handy thing to have, but if you add it onto a zone play, and build from there, you can very easily make simple and easy to remember plays for your offense, but give the defense a multitude of things to worry about.

You can also take the ideas shown above and build on them. What if instead of running the Bubble to the backside, we get the outside receiver to run a fade? You can see how quickly things can open up.

I realise this was a long article, and appreciate you taking the time to go through. I’d love to hear your thoughts on some of the ideas I’ve discussed, and once again a massive thanks to Coach McCusker for helping out with this article.